the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

Flying for France: The Story of the American Volunteers With the French Airforce

|

Our daily routine goes on with little change. Whenever the weather permits--that is, when it isn't raining, and the clouds aren't too low--we fly over the Verdun battlefield at the hours dictated by General Headquarters. As a rule the most successful sorties are those in the early morning. We are called while it's still dark. Sleepily I try to reconcile the French orderly's muttered, C'est l'heure, monsieur, that rouses me from slumber, with the strictly American words and music of "When That Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam'" warbled by a particularly wide-awake pilot in the next room. A few minutes later, having swallowed some coffee, we motor to the field. The east is turning gray as the hangar curtains are drawn apart and our machines trundled out by the mechanicians. All the pilots whose planes are in commission--save those remaining behind on guard--prepare to leave. We average from four to six on a sortie, unless too many flights have been ordered for that day, in which case only two or three go out at a time. Now the east is pink, and overhead the sky has changed from gray to pale blue. It is light enough to fly. We don our fur-lined shoes and combinations and adjust the leather flying hoods and goggles. A good deal of conversation occurs--perhaps because, once aloft, there's nobody to talk to. "Eh, you," one pilot cries jokingly to another, "I hope some Boche just ruins you this morning, so I won't have to pay you the fifty francs you won from me last night!" This financial reference concerns a poker game. "You do, do you?" replies the other as he swings into his machine. "Well, I'd be glad to pass up the fifty to see you landed by the Boches. You'd make a fine sight walking down the street of some German town in those wooden shoes and pyjama pants. Why don't you dress yourself? Don't you know an aviator's supposed to look chic?" A sartorial eccentricity on the part of one of our colleagues is here referred to. The raillery is silenced by a deafening roar as the motors are tested. Quiet is briefly restored, only to be broken by a series of rapid explosions incidental to the trying out of machine guns. You loudly inquire at what altitude we are to meet above the field. "Fifteen hundred metres--go ahead!" comes an answering yell. Essence et gaz! [Oil and gas!] you call to your mechanician, adjusting your gasolene and air throttles while he grips the propeller. Contact! he shrieks, and Contact! you reply. You snap on the switch, he spins the propeller, and the motor takes. Drawing forward out of line, you put on full power, race across the grass and take the air. The ground drops as the hood slants up before you and you seem to be going more and more slowly as you rise. At a great height you hardly realize you are moving. You glance at the clock to note the time of your departure, and at the oil gauge to see its throb. The altimeter registers 650 feet. You turn and look back at the field below and see others leaving.

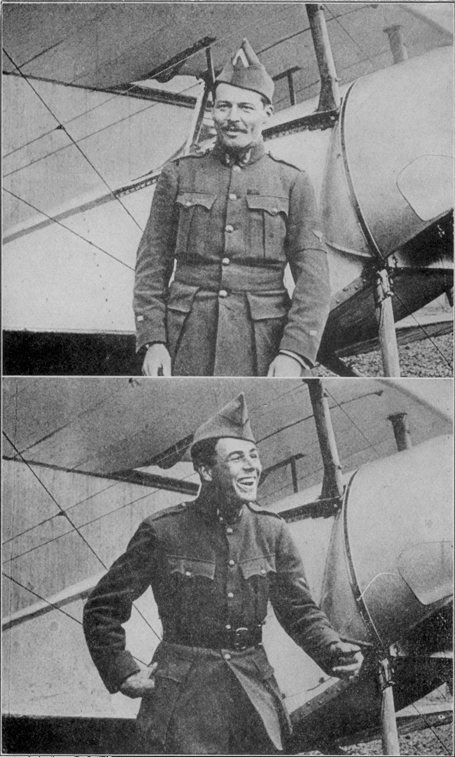

Two Members of the American Escadrille. In three minutes you are at about 4,000 feet. You have been making wide circles over the field and watching the other machines. At 4,500 feet you throttle down and wait on that level for your companions to catch up. Soon the escadrille is bunched and off for the lines. You begin climbing again, gulping to clear your ears in the changing pressure. Surveying the other machines, you recognize the pilot of each by the marks on its side--or by the way he flies. The distinguishing marks of the Nieuports are various and sometimes amusing. Bert Hall, for instance, has BERT painted on the left side of his plane and the same word reversed (as if spelled backward with the left hand) on the right--so an aviator passing him on that side at great speed will be able to read the name without difficulty, he says! The country below has changed into a flat surface of varicoloured figures. Woods are irregular blocks of dark green, like daubs of ink spilled on a table; fields are geometrical designs of different shades of green and brown, forming in composite an ultra-cubist painting; roads are thin white lines, each with its distinctive windings and crossings--from which you determine your location. The higher you are the easier it is to read. In about ten minutes you see the Meuse sparkling in the morning light, and on either side the long line of sausage-shaped observation balloons far below you. Red-roofed Verdun springs into view just beyond. There are spots in it where no red shows and you know what has happened there. In the green pasture land bordering the town, round flecks of brown indicate the shell holes. You cross the Meuse. |