the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

the Archive of World War 1 Photographs and Texts

Flying for France: The Story of the American Volunteers With the French Airforce

|

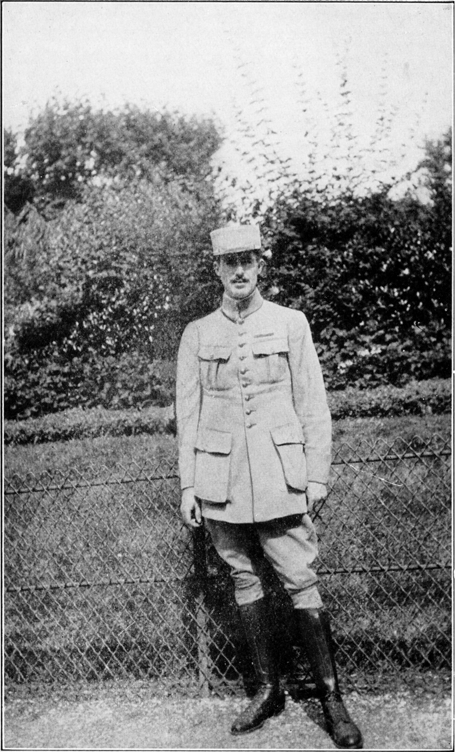

Kiffin Rockwell. No greater blow could have befallen the escadrille. Kiffin was its soul. He was loved and looked up to by not only every man in our flying corps but by every one who knew him. Kiffin was imbued with the spirit of the cause for which he fought and gave his heart and soul to the performance of his duty. He said: "I pay my part for Lafayette and Rochambeau," and he gave the fullest measure. The old flame of chivalry burned brightly in this boy's fine and sensitive being. With his death France lost one of her most valuable pilots. When he was over the lines the Germans did not pass--and he was over them most of the time. He brought down four enemy planes that were credited to him officially, and Lieutenant de Laage, who was his fighting partner, says he is convinced that Rockwell accounted for many others which fell too far within the German lines to be observed. Rockwell had been given the Médaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre, on the ribbon of which he wore four palms, representing the four magnificent citations he had received in the order of the army. As a further reward for his excellent work he had been proposed for promotion from the grade of sergeant to that of second lieutenant. Unfortunately the official order did not arrive until a few days following his death. The night before Rockwell was killed he had stated that if he were brought down he would like to be buried where he fell. It was impossible, however, to place him in a grave so near the trenches. His body was draped in a French flag and brought back to Luxeuil. He was given a funeral worthy of a general. His brother, Paul, who had fought in the Legion with him, and who had been rendered unfit for service by a wound, was granted permission to attend the obsequies. Pilots from all near-by camps flew over to render homage to Rockwell's remains. Every Frenchman in the aviation at Luxeuil marched behind the bier. The British pilots, followed by a detachment of five hundred of their men, were in line, and a battalion of French troops brought up the rear. As the slow moving procession of blue and khaki-clad men passed from the church to the graveyard, airplanes circled at a feeble height above and showered down myriads of flowers. Rockwell's death urged the rest of the men to greater action, and the few who had machines were constantly after the Boches. Prince brought one down. Lufbery, the most skillful and successful fighter in the escadrille, would venture far into the enemy's lines and spiral down over a German aviation camp, daring the pilots to venture forth. One day he stirred them up, but as he was short of fuel he had to make for home before they took to the air. Prince was out in search of a combat at this time. He got it. He ran into the crowd Lufbery had aroused. Bullets cut into his machine and one exploding on the front edge of a lower wing broke it. Another shattered a supporting mast. It was a miracle that the machine did not give way. As badly battered as it was Prince succeeded in bringing it back from over Mulhouse, where the fight occurred, to his field at Luxeuil. The same day that Prince was so nearly brought down Lufbery missed death by a very small margin. He had taken on more gasoline and made another sortie. When over the lines again he encountered a German with whom he had a fighting acquaintance. That is he and the Boche, who was an excellent pilot, had tried to kill each other on one or two occasions before. Each was too good for the other. Lufbery manoeuvred for position but, before he could shoot, the Teuton would evade him by a clever turn. They kept after one another, the Boche retreating into his lines. When they were nearing Habsheim, Lufbery glanced back and saw French shrapnel bursting over the trenches. It meant a German plane was over French territory and it was his duty to drive it off. Swooping down near his adversary he waved good-bye, the enemy pilot did likewise, and Lufbery whirred off to chase the other representative of Kultur. He caught up with him and dove to the attack, but he was surprised by a German he had not seen. Before he could escape three bullets entered his motor, two passed through the fur-lined combination he wore, another ripped open one of his woolen flying boots, his airplane was riddled from wing tip to wing tip, and other bullets cut the elevating plane. Had he not been an exceptional aviator he never would have brought safely to earth so badly damaged a machine. It was so thoroughly shot up that it was junked as being beyond repairs. Fortunately Lufbery was over French territory or his forced descent would have resulted in his being made prisoner. I know of only one other airplane that was safely landed after receiving as heavy punishment as did Lufbery's. It was a two-place Nieuport piloted by a young Frenchman named Fontaine with whom I trained. He and his gunner attacked a German over the Bois le Pretre who dove rapidly far into his lines. Fontaine followed and in turn was attacked by three other Boches. He dropped to escape, they plunged after him forcing him lower. He looked and saw a German aviation field under him. He was by this time only 2,000 feet above the ground. Fontaine saw the mechanics rush out to grasp him, thinking he would land. The attacking airplanes had stopped shooting. Fontaine pulled on full power and headed for the lines. The German planes dropped down on him and again opened fire. They were on his level, behind and on his sides. Bullets whistled by him in streams. The rapid-fire gun on Fontaine's machine had jammed and he was helpless. His gunner fell forward on him, dead. The trenches were just ahead, but as he was slanting downward to gain speed he had lost a good deal of height, and was at only six hundred feet when he crossed the lines, from which he received a ground fire. The Germans gave up the chase and Fontaine landed with his dead gunner. His wings were so full of holes that they barely supported the machine in the air. The uncertain wait at Luxeuil finally came to an end on the 12th of October. The afternoon of that day the British did not say: "Come on Yanks, let's call off the war and have tea," as was their wont, for the bombardment of Oberndorf was on. The British and French machines had been prepared. Just before climbing into their airplanes the pilots were given their orders. The English in their single-seated Sopwiths, which carried four bombs each, were the first to leave. The big French Brequets and Farmans then soared aloft with their tons of explosive destined for the Mauser works. The fighting machines, which were to convoy them as far as the Rhine, rapidly gained their height and circled above their charges. Four of the battleplanes were from the American escadrille. They were piloted respectively by Lieutenant de Laage, Lufbery, Norman Prince, and Masson. The Germans were taken by surprise and as a result few of their machines were in the air. The bombardment fleet was attacked, however, and six of its planes shot down, some of them falling in flames. Baron, the famous French night bombarder, lost his life in one of the Farmans. Two Germans were brought down by machines they attacked and the four pilots from the American escadrille accounted for one each. Lieutenant de Laage shot down his Boche as it was attacking another French machine and Masson did likewise. Explaining it afterward he said: "All of a sudden I saw a Boche come in between me and a Breguet I was following. I just began to shoot, and darned if he didn't fall." As the fuel capacity of a Nieuport allows but little more than two hours in the air the avions de chasse were forced to return to their own lines to take on more gasoline, while the bombardment planes continued on into Germany. The Sopwiths arrived first at Oberndorf. Dropping low over the Mauser works they discharged their bombs and headed homeward. All arrived, save one, whose pilot lost his way and came to earth in Switzerland. When the big machines got to Oberndorf they saw only flames and smoke where once the rifle factory stood. They unloaded their explosives on the burning mass. The Nieuports having refilled their tanks went up to clear the air of Germans that might be hovering in wait for the returning raiders. Prince found one and promptly shot it down. Lufbery came upon three. He drove for one, making it drop below the others, then forcing a second to descend, attacked the one remaining above. The combat was short and at the end of it the German tumbled to earth. This made the fifth enemy machine which was officially credited to Lufbery. When a pilot has accounted for five Boches he is mentioned by name in the official communication, and is spoken of as an "Ace," which in French aërial slang means a super-pilot. Papers are allowed to call an "ace" by name, print his picture and give him a write-up. The successful aviator becomes a national hero. When Lufbery worked into this category the French papers made him a head liner. The American "Ace," with his string of medals, then came in for the ennuis of a matinee idol. The choicest bit in the collection was a letter from Wallingford, Conn., his home town, thanking him for putting it on the map. Darkness was coming rapidly on but Prince and Lufbery remained in the air to protect the bombardment fleet. Just at nightfall Lufbery made for a small aviation field near the lines, known as Corcieux. Slow-moving machines, with great planing capacity, can be landed in the dark, but to try and feel for the ground in a Nieuport, which comes down at about a hundred miles an hour, is to court disaster. Ten minutes after Lufbery landed Prince decided to make for the field. He spiraled down through the night air and skimmed rapidly over the trees bordering the Corcieux field. In the dark he did not see a high-tension electric cable that was stretched just above the tree tops. The landing gear of his airplane struck it. The machine snapped forward and hit the ground on its nose. It turned over and over. The belt holding Prince broke and he was thrown far from the wrecked plane. Both of his legs were broken and he naturally suffered internal injuries. In spite of the terrific shock and his intense pain Prince did not lose consciousness. He even kept his presence of mind and gave orders to the men who had run to pick him up. Hearing the hum of a motor, and realizing a machine was in the air, Prince told them to light gasoline fires on the field. "You don't want another fellow to come down and break himself up the way I've done," he said. Lufbery went with Prince to the hospital in Gerardmer. As the ambulance rolled along Prince sang to keep up his spirits. He spoke of getting well soon and returning to service. It was like Norman. He was always energetic about his flying. Even when he passed through the harrowing experience of having a wing shattered, the first thing he did on landing was to busy himself about getting another fitted in place and the next morning he was in the air again. No one thought that Prince was mortally injured but the next day he went into a coma. A blood clot had formed on his brain. Captain Haff in command of the aviation groups of Luxeuil, accompanied by our officers, hastened to Gerardmer. Prince lying unconscious on his bed, was named a second lieutenant and decorated with the Legion of Honor. He already held the Médaille Militaire and Croix de Guerre. Norman Prince died on the 15th of October. He was brought back to Luxeuil and given a funeral similar to Rockwell's. It was hard to realize that poor old Norman had gone. He was the founder of the American escadrille and every one in it had come to rely on him. He never let his own spirits drop, and was always on hand with encouragement for the others. I do not think Prince minded going. He wanted to do his part before being killed, and he had more than done it. He had, day after day, freed the line of Germans, making it impossible for them to do their work, and three of them he had shot to earth. Two days after Prince's death the escadrille received orders to leave for the Somme. The night before the departure the British gave the American pilots a farewell banquet and toasted them as their "Guardian Angels." They keenly appreciated the fact that four men from the American escadrille had brought down four Germans, and had cleared the way for their squadron returning from Oberndorf. When the train pulled out the next day the station platform was packed by khaki-clad pilots waving good-bye to their friends the "Yanks." The escadrille passed through Paris on its way to the Somme front. The few members who had machines flew from Luxeuil to their new post. At Paris the pilots were reënforced by three other American boys who had completed their training. They were: Fred Prince, who ten months before had come over from Boston to serve in aviation with his brother Norman; Willis Haviland, of Chicago, who left the American Ambulance for the life of a birdman, and Bob Soubrian, of New York, who had been transferred from the Foreign Legion to the flying corps after being wounded in the Champagne offensive. Before its arrival in the Somme the escadrille had always been quartered in towns and the life of the pilots was all that could be desired in the way of comforts. We had, as a result, come to believe that we would wage only a de luxe war, and were unprepared for any other sort of campaign. The introduction to the Somme was a rude awakening. Instead of being quartered in a villa or hotel, the pilots were directed to a portable barracks newly erected in a sea of mud. It was set in a cluster of similar barns nine miles from the nearest town. A sieve was a watertight compartment in comparison with that elongated shed. The damp cold penetrated through every crack, chilling one to the bone. There were no blankets and until they were procured the pilots had to curl up in their flying clothes. There were no arrangements for cooking and the Americans depended on the other escadrilles for food. Eight fighting units were located at the same field and our ever-generous French comrades saw to it that no one went hungry. The thick mist, for which the Somme is famous, hung like a pall over the birdmen's nest dampening both the clothes and spirits of the men. Something had to be done, so Thaw and Masson, who is our Chef de Popote (President of the Mess) obtained permission to go to Paris in one of our light trucks. They returned with cooking utensils, a stove, and other necessary things. All hands set to work and as a result life was made bearable. In fact I was surprised to find the quarters as good as they were when I rejoined the escadrille a couple of weeks after its arrival in the Somme. Outside of the cold, mud, and dampness it wasn't so bad. The barracks had been partitioned off into little rooms leaving a large space for a dining hall. The stove is set up there and all animate life from the lion cub to the pilots centre around its warming glow. The eight escadrilles of fighting machines form a rather interesting colony. The large canvas hangars are surrounded by the house tents of their respective escadrilles; wooden barracks for the men and pilots are in close proximity, and sandwiched in between the encampments of the various units are the tents where the commanding officers hold forth. In addition there is a bath house where one may go and freeze while a tiny stream of hot water trickles down one's shivering form. Another shack houses the power plant which generates electric light for the tents and barracks, and in one very popular canvas is located the community bar, the profits from which go to the Red Cross. We had never before been grouped with as many other fighting escadrilles, nor at a field so near the front. We sensed the war to better advantage than at Luxeuil or Bar-le-Duc. When there is activity on the lines the rumble of heavy artillery reaches us in a heavy volume of sound. From the field one can see the line of sausage-shaped observation balloons, which delineate the front, and beyond them the high-flying airplanes, darting like swallows in the shrapnel puffs of anti-air-craft fire. The roar of motors that are being tested, is punctuated by the staccato barking of machine guns, and at intervals the hollow whistling sound of a fast plane diving to earth is added to this symphony of war notes. |